In the heart of Lagos, Nigeria — a city full of history and culture — thousands of old photographs were being forgotten. Stored in rice sacks, cardboard boxes, or sometimes even burned, these pictures told the everyday stories of people’s lives, now fading under heat, humidity, and time.

Two artists — Karl Ohiri, a British-Nigerian photographer, and Riikka Kassinen, a Finnish artist — decided to do something about it.

A Race Against Time

Lagos was once filled with vibrant photography studios. From the 1960s to the early 2000s, they captured weddings, birthdays, portraits, and street life. But as the original photographers retired, passed away, or moved on, their photo archives were abandoned or destroyed.

Karl Ohiri couldn’t ignore what he saw.

“It was history being erased,” he said in an interview.

So, he and Riikka launched the Lagos Studio Archives, a project dedicated to recovering, restoring, and preserving the photographic legacy of Lagos.

Over the past nine years, the pair has been tracking down former studios and collecting negatives — many of them damaged by time and weather. They now hold an estimated 100,000+ negatives, although the exact number is unknown. Some photos are scratched or moldy. Others are too far gone to fully repair.

Despite the damage, these photos have been turned into powerful artworks — including the series “Archive of Becoming”, which was shown at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York.

A Glimpse Into the Past

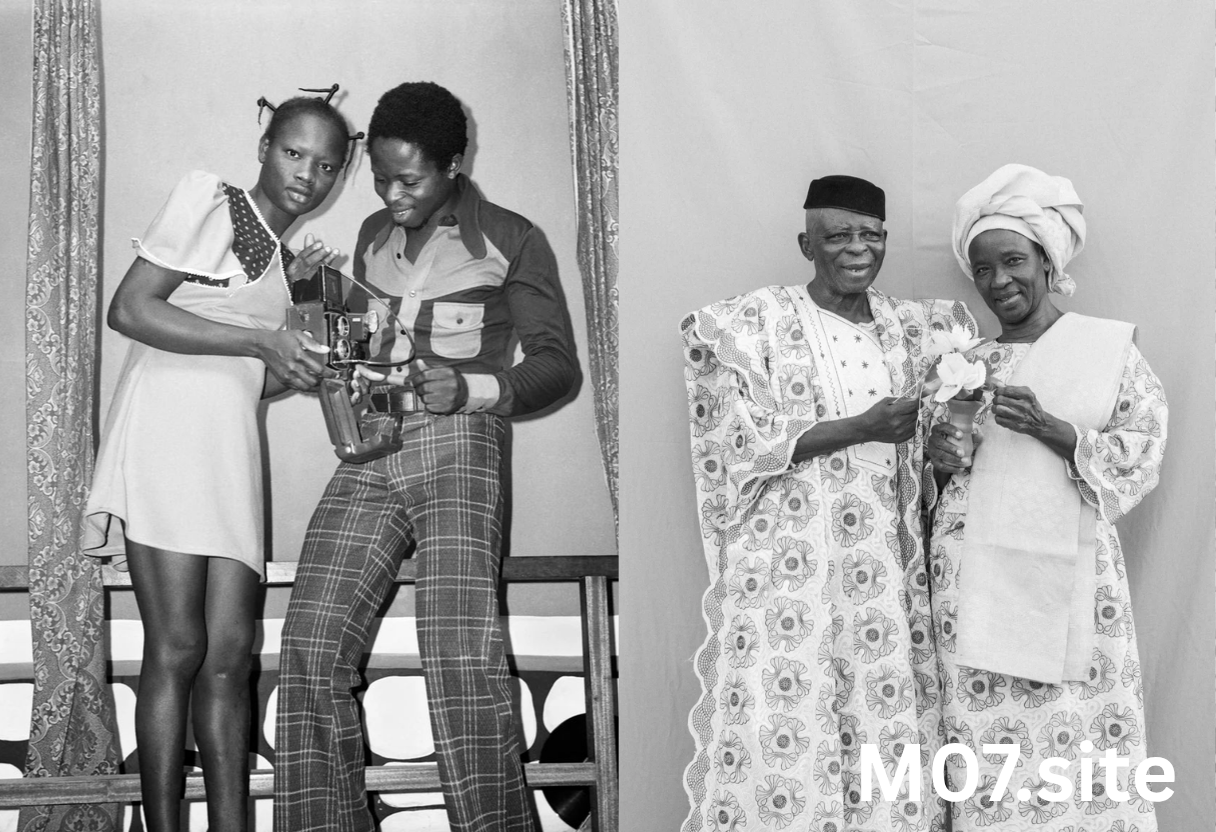

These photos tell the story of Lagos through the decades. In one image, a woman poses in front of a backdrop of Mecca. In another, a man proudly shows off his new cassette player. There are black-and-white portraits of men in bell-bottoms, street scenes from the 1970s, and colorful moments from family events.

“These studios were more than businesses,” Ohiri explained. “They were spaces where people could express who they were, their hopes, and achievements.”

In the UK or U.S., museums often preserve such archives. But in Lagos, no such system existed — until now.

The People Behind the Lens

One of the most moving parts of the archive is the collection from Abi Morocco Photos, a husband-and-wife photography duo — John and Funmilayo Abe — who worked from the early 1970s to 2006.

They ran a studio in Shogunle, Lagos, and also photographed events in homes and on the streets. John passed away in 2024, but their work lives on through the archive. An exhibition of their photos was recently held in London’s Autograph Gallery, and a book is in the works.

Their story is just one of many hidden within the negatives.

Challenges and Discoveries

Digitally restoring these photos is slow, careful work. Each negative can take hours to clean, correct, and scan. Some are too far gone — covered in mold or chemicals from the film’s decay.

“Sometimes we arrived too late,” said Ohiri. “Photographers with decades of work — all of it gone. It only takes seconds to destroy a lifetime of history.”

In many cases, the original subjects are unknown. The artists have never met anyone in the photos, though once, a friend recognized his uncle in one of them. That’s their hope — that people will one day identify the faces, reuniting families with pieces of their personal history.

“We want the archive to become a family album for Lagos,” said Kassinen.

What’s Next for the Archive

Though much of their work is being shown internationally — from London to New York — the goal is to make it accessible to Lagosians. The team is planning books, exhibitions, and a new focus on female photographers who’ve also been overlooked.

The challenge remains massive. The negatives are stored in their studio in Helsinki, Finland, and the work of scanning, sorting, and restoring them could take a lifetime — or more.

But for Ohiri and Kassinen, it’s worth it.

“These photographs aren’t just images,” Ohiri said. “They’re living memory — proof that these people, these moments, these dreams existed.”